With global leverage reaching new peaks and a higher cost of debt, can governments, corporates and households finance climate, digital and demographic transition? Published below is an insert of S&P Global’s report: Global debt 2030: Can the world afford a multifaceted transition?

US$37 trillion needed to finance transition over 2024–2030

The cost of climate inaction is substantial. Lower- and lower-middle-income countries face up to 12% of GDP being at risk of physical hazard losses by 2050 under a slow transition scenario and absent adaptation. Meanwhile, the challenge of energy security, affordability and sustainability looks very different in developing economies than in Europe and the US, where per capita incomes are as much as 40 times higher. Concurrently, IT advances are continuing apace, e.g., Generative AI, requiring governments and corporates to make further investment. On the societal front, many countries are facing an increasingly aging population, which could stymie further economic growth. There is a cost in caring for such aging populations.

Besides the baseline scenario described above, we have developed a supplemental “cost of transition” scenario that assumes additional debt (over the baseline) is raised to fund climate mitigation and adaptation, digital transformation and an aging population. We have not compared results with other development pathways that countries might take, which could be more costly than this transition scenario (e.g., failure to act on climate change).

Climate financing takes up the largest share of debt for transition. We estimate that a cumulative US$37 trillion of debt — US$25 trillion for climate, US$7 trillion for digital transformation and US$5 trillion for aging — may have to be raised between 2024 and 2030 (see chart). In arriving at these transition sums, we have used a variety of proprietary and external sources.

We acknowledge that there is always a high degree of uncertainty in such estimates and variability in ranges of estimates for this financing gap. For example, we note that more recent estimates around climate scenarios suggest higher financing needs or wider gaps. Also, other sources such as taxes, including a carbon tax and equity financing could contribute to financing gaps. Nonetheless, the proposed transition scenario represents in our view a reasonable midrange estimate to support our discussion.

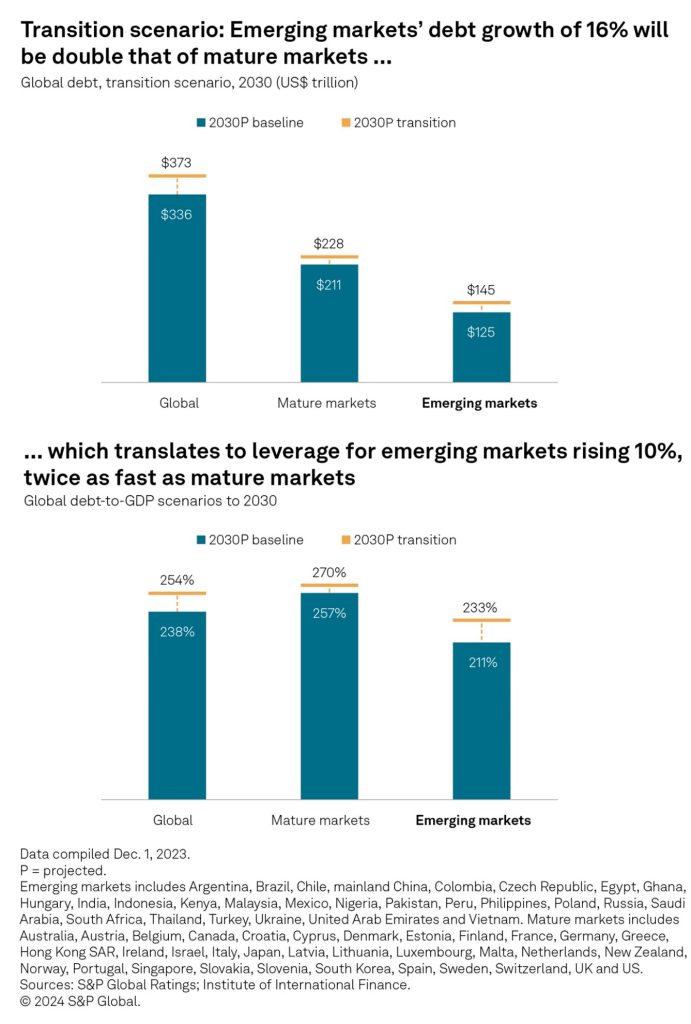

Cost of transition could push leverage up another 7%. In our scenario, absolute debt could grow to US$373 trillion between 2023 and 2030, 11% more than the baseline US$336 trillion. This translates to the global debt-to-GDP ratio rising to 254%, 7% more than the baseline 238% (see chart). Because the weight of physical risk falls disproportionately on low- and low-middle-income countries we see the absolute debt and, consequently, the debt-to-GDP leverage rising faster for emerging markets than for mature markets (see charts below). The lower-income cohort of our emerging markets sample (classified as lower-middle-income economies by the World Bank) could fare even worse; they may see absolute debt increase 19% and debt-to-GDP jump 14% in the transition scenario compared with the baseline.